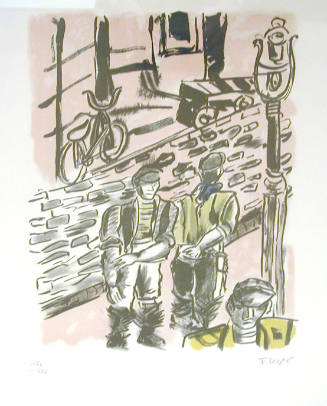

Fernand Leger

Feb 04, 1881 - Aug 17, 1955 Fernand Leger was a French painter, draughtsman, illustrator, printmaker, stage designer, film maker and ceramicist. Among the most prominent artists in Paris in the first half of the 20th century, he was prolific in many media and articulated a consistent position on the role of art in society in his many lectures and writings. His mature work underwent many changes, from a Cubist-derived abstraction in the 1910s to distinctive realist imagery in the 1950s. Léger attracted numerous students to his various schools, and his ideas and philosophy were disseminated by modern artists throughout Europe and the Americas.

2. Working methods and technique.

Throughout his career Léger’s working practice was to produce groups of works (drawings, gouaches and even oil paintings) relating to specific themes, a method that encouraged the production of series from 1910. Although drawing represented his only artistic activity during World War I, it later became primarily important to him as a preliminary stage in his work and his teaching method. Careful preparatory drawings exist for works in virtually every medium, and selected versions were often then gridded for enlarging on canvas in a definitive version in oil. This was particularly true for his work after World War II, although some of his preparatory studies of 1923–4 are also remarkably finished. The preparatory drawings themselves would often evolve from loose sketches, but Léger was always careful to distinguish between the two. Some of his drawings from the 1940s, for example, show a freedom and boldness that suggest a renewed interest in draughtsmanship for its own sake about this time. The canvases emerged naturally from this process, with some themes being represented by several paintings as equally valid variations, while in other instances various treatments in oil, sometimes differing only in minute details, were seen only as part of the process of working towards a definitive image, as in the series leading to Le Grand Déjeuner. The essentially mechanical approach adopted by Léger towards his paintings is further demonstrated by his tendency to reuse certain standard elements, such as a pair of hands or lips, not just in treatments of related subjects but also in paintings and drawings on different themes.

Léger often used his students to paint his large-scale works. Academy pupils of the 1920s such as the Swedish artist Otto Carlsund recalled executing versions of Léger’s paintings and several of his set designs. In the 1930s Léger used his students to help conceive and execute designs for Naissance d’une cité (1937) and to paint his mural for the Palais de la Découverte; among the students contributing to the latter was the Danish artist Asger Jorn. In the early 1950s Léger’s students painted panels for the book festival of the 1953 Comité National d’Ecrivains. One of his former students, Bruce Gregory (b 1917), executed Léger’s 1952 gouaches on a large scale as paintings for the east and west walls of the General Assembly of the United Nations in New York.

Léger’s experiments with film, particularly the Ballet mécanique, reflect his enthusiasm with energetic, mechanized modernity. Although innovative, his films, like his response to the movements of the body in his designs for the ballet, were more concerned with formal aspects than with technical experiments. In his experiments with other media, his interest was again seldom purely technical. Indeed, in most cases his choice of a particular medium (mosaic, ceramics, stained glass) was based on its suitability for the monumental public display of his pre-conceived designs.

i) Early years, to 1909.

Born in rural Normandy, Léger often said that he was of ‘peasant stock’. Although his father was a cattle merchant, Léger was sent by his family to Caen in 1897 to be an apprentice in an architect’s office, where he remained until 1899. In 1900 he went to Paris and again worked in an architect’s office as a draughtsman. After compulsory military service in 1902, when he was sent to Versailles with a corps of engineers, Léger was admitted in 1903 to the Ecole des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, but not to the more prestigious Ecole des Beaux-Arts. He studied under Jean-Léon Gérôme and Gabriel Ferrier (1847–1914) and began to visit the Académie Julian and the Musée du Louvre regularly, although he continued to work in an architect’s office, earning additional money retouching photographs for a commercial photographer. From 1904 to 1906 he shared a flat with a friend from Argentan, the designer and painter André Mare (1885–1932), with whom he would maintain a detailed correspondence until the early 1920s.

Between 1906 and 1908 Léger made four trips to Corsica, while also beginning to frequent avant-garde gatherings in Paris; by 1908 he was living at LA RUCHE, near Montparnasse, where he met many young artists, including Robert Delaunay, Marc Chagall, Chaïm Soutine, Henri Laurens and Jacques Lipchitz, as well as the poets Max Jacob, Guillaume Apollinaire, Pierre Reverdy, Maurice Raynal and Blaise Cendrars. His paintings of this period reveal the wide-ranging influences that Léger had absorbed and show a progression from early works, with a strongly impressionist flavour (e.g. My Mother’s Garden, 1905; Biot, Mus. N. Fernand Léger), through brief Neo-Impressionist- and Fauve-inspired phases to an increasing concern with volumes and order, influenced by his visit and strong response to the memorial exhibition of Cézanne’s work at the Salon d’Automne of 1907. Léger destroyed most of his work of pre-1910, and the examples that remain, comprising a few paintings (housed principally in the Musée National Fernand Léger, Biot) and a number of ink drawings, are characterized by a subdued impressionist palette in his painted landscapes, nudes and portraits and by a calligraphic quality in his drawings.

(ii) 1910–17.

Although Léger had exhibited at the Salon d’Automne of 1909 with Constantin Brancusi, Marcel Duchamp, Roger de La Fresnaye, Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger and Francis Picabia, it was not until 1910 that his association with these avant-garde artists became marked and influential on his work. He joined Delaunay, Gleizes, Metzinger and Henri Le Fauconnier at meetings at Jacques Villon’s studio in Puteaux, where the Section d’Or was founded. At this time Léger began to paint in a markedly Cubist style, distinguished from that of Picasso and Braque by its modelling of volumes and its slightly obscured but relatively accessible imagery. In 1910 he began the series Smoke on the Roofs, in which he concentrated on the value of volumetric contrasts with a minimum of chromatic variation, a preoccupation that lasted until the end of 1914. ‘Contrast = dissonance’, he wrote in an article of 1914 (‘Les Révélations picturales actuelles’, repr. in Functions of Painting, pp. 11–19), ‘and hence a maximum expressive effect’. Referring to this series, he noted:

I will take as an example a commonplace subject: the visual effect of curled and round puffs of smoke rising between houses. You want to convey their plastic value. Here you have the best example on which to apply research into multiplicative intensities. Concentrate your curves with the greatest possible variety without breaking up their mass; frame them by means of the hard, dry relationship of the surfaces of the houses, dead surfaces that will acquire movement by being coloured in contrast to the central mass and being opposed by live forms; you will obtain a maximum effect.

His large-scale paintings of The Wedding (2.57?2.06 m, 1910–11; Paris, Pompidou; see Cubism, fig. 2) and Nudes in a Forest (1.2?1.7 m, 1911; Otterlo, Rijksmus. Kröller-Müller; see fig. 1) are culminations of this early research into contrasts.

In 1912 Léger participated in the Maison Cubiste, a part of the decorative arts section organized by his friend André Mare for the Salon d’Automne of 1912. Viewers entered the Maison Cubiste through a façade designed by Raymond Duchamp-Villon, leading to a domestic interior featuring the latest in contemporary design. Léger’s Level Crossing (1912; Basle, Gal. Beyeler) was among the paintings by young artists associated with Cubism that graced the interior walls. His participation in this venture secured his position among the avant-garde of his generation. The following year Léger signed a three-year, exclusive contract with Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, already established as the dealer of Picasso and Braque’s work. Kahnweiler purchased all the paintings as well as 50 drawings from Léger’s studio. By this time Léger was devoting himself fully to the issue of contrasts in his paintings in a series known as the Contrasts of Forms. His canvases were dominated by convex and concave volumes, accentuated by touches of primary and secondary colours. In a lecture of 1913 to the Académie Wassilieff (repr. in Functions of Painting, pp. 3–10) in Paris, he declared ‘Pictorial contrasts used in their purest sense (complementary colours, lines and forms) are henceforth the structural basis of modern pictures’. Léger’s fascination with contrasts emerged from his awareness that he was living in a vastly accelerated, dynamic world and that the rapid changes in contemporary life were jarring and unsettling to much of society; he sought to challenge the viewer and allow his art to conform to the pace of the world around him.

Léger’s study of contrasts was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I. He was drafted in August 1914 and served in the Argonne until late 1915. Following a brief leave, during which he saw new films by Charlie Chaplin, accompanied by Guillaume Apollinaire, and also met his first wife, Jeanne Lohy, he returned to serve with the engineering corps at the Verdun and Fort Douamont battlefields. While serving at Verdun in September 1916 Léger was gassed, and he was hospitalized at Villepinte, near Paris, until the end of 1917. Throughout Léger’s service at the front and his subsequent hospitalization, he produced a considerable number of drawings, gouaches and several paintings. His War Drawings, made on every conceivable surface available to him, chronicle life at the front: the leisure activities of the soldiers, preparations for battle and the conditions in the trenches (e.g. Soldiers in a Dugout, 1915; priv. col., see Cassou and Leymarie, no. 39). He gained a new appreciation for the ‘machine gun or the breech of a 75’, which were ‘more worth painting’, Léger noted, ‘than four apples on a table or a Saint-Cloud landscape’. The experience at the front transformed him; Léger felt he had finally encountered ‘the people’, and his art had to be accessible and relevant to them. In 1922 he decided that he would now model in pure and local colour, using large volumes, disdaining ‘tasteful arrangements, delicate shading, and dead backgrounds’. Léger’s The Card Game (1917; Otterlo, Rijksmus. Kröller-Müller), paying homage to his earliest hero, Cézanne, and suggestive of the changes to appear in his own subsequent work, fused the contrasts of his pre-war work with his post-war concern for the ordinary man. The painting is based on studies he made at the front of soldiers playing cards; in its style and content it marks a transition between Léger’s early mature work of the 1910s and his machine-oriented pictures of the 1920s.

(iii) 1918–26.

Léger’s return to Paris coincided with a radical shift in his imagery. He produced a number of paintings on each of several specific themes, such as The Discs, The Propellers and The Circus. Machine-inspired imagery dominated; elements were densely packed and brightly coloured. For Léger the mechanical element was ‘not a fixed position, an attitude, but a means of succeeding in conveying a feeling of strength and power…. It is necessary to retain what is useful in the subject and to extract from it the best part possible. I try to create a beautiful object with mechanical elements’. His mechanical elements were partly derived from his wartime experience and his awe at military hardware and its power. Léger graphically illustrated Blaise Cendrars’s book J’ai tué (Paris, 1918) with tubular soldiers and sleek machines. His illustrations for Cendrars’s prose-poem La Fin du monde filmée par l’ange Notre-Dame (Paris, 1919) prefigured his monumental painting of The City (1919; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.; see fig. 2). The artist’s fascination with the dynamism of Paris and the visual landscape of advertising hoardings, kiosks and illuminated signs unite in this painting. Within a quasi-Cubist armature faceless cut-out figures hover amid intersecting planes of coloured walls, cropped signs and metal railings and towers. Colours were unmodulated and bold; in 1946 Léger reflected that in The City pure colour had been incorporated into a geometric design to the greatest possible extent and that it was modern advertising that had first understood the importance of this new purity.

Léger’s pre-war dealer, Kahnweiler, had been forced to abandon his gallery during the war years because of his German ancestry; his impressive collection of avant-garde art was sold during the 1920s at public sales in Paris. Like Kahnweiler’s other artists, Léger sought a new dealer in the post-war years, and in July 1918 he signed a contract with Léonce Rosenberg, who showed Léger’s work for the first time in a one-man exhibition at the new Galerie de l’Effort Moderne in 1919. In the same year Léger married Jeanne Lohy.

Although his work in the early 1920s continued the mechanical themes of the years immediately following the war, the figure also reappeared in Léger’s work at this time. His paintings of The Mechanic (e.g. 1920; Ottawa, N.G.) depict a working man with what appear to be machine-made parts; in his paintings of women, especially in his paintings of 1921 devoted to Le Grand Déjeuner (final version in New York, MOMA), Léger invoked classicism in his quest to find monumental figures for his imagery. In pursuing this direction Léger’s work very much paralleled Picasso’s classicism of the same years. Building on themes of odalisques and languid nudes in elaborate settings found in the works of David, Ingres and Puvis de Chavannes, Léger created more solid, less fleshy figures and situated them amid the objects and décor of a domestic bourgeois interior. Léger’s interest in Classical subject-matter and his passion for medieval and Renaissance art took him to Venice and Ravenna with his dealer, Rosenberg, in 1924. A substantial number of paintings in Léger’s work of the early 1920s were also devoted to the Animated Landscape (version 1921; Montreal, priv. col., see de Francia, pl. 18). These were depictions of the rural settings familiar to him from his childhood and of what he considered to be the welcome intrusion of contemporary life in them.

Léger’s wartime experience encouraged him in the early 1920s to explore diverse media in order to reach the wide range of people that he had encountered during his years in the trenches. He became interested in printmaking around this time, although after a brief period of activity this interest waned, and also in book illustration as a vehicle to disseminate his ideas to wider audiences. Another means was the cinema, which Léger had particularly admired ever since he had first encountered Chaplin’s films during the war. In 1920 he illustrated a book of poems devoted to Chaplin, Ivan Goll’s Die Chaplinade (Dresden and Berlin, 1920). In the following year he assisted Blaise Cendrars, who was working for film maker Abel Gance on La Roue. Léger appears to have participated in the creation, with Cendrars, of the fast-paced montage sections of the film, which received considerable attention in the press. Léger produced a promotional poster for the film and wrote an article in which he celebrated Gance’s use of a mechanical object—the wheel of a train—as one of the principal characters in the film. Stimulated by his appreciation for Gance’s achievement, Léger embarked on his own films. Initially he proposed several versions of an animated cartoon of Charlot Cubiste (Cubist Chaplin). Then he created sets for the laboratory section of Marcel L’Herbier’s film L’Inhumaine (1923).

Ballet mécanique (1924) was the first film project realized principally by Léger. He was assisted technically by the American film maker Dudley Murphy, who at the suggestion of Ezra Pound had approached Léger with a proposal to make a film together. Ballet mécanique consisted of a rapid succession of mechanical images alternating with close-ups of faces, body parts, pots and pans, abstract shapes, and walking and swinging women. Léger wrote that in it he had set out to prove that it was possible to make a visually interesting film using only simple objects and fragments of objects, ‘of a mechanical element, of rhythmic repetitions copied from certain objects of a commonplace nature and “artistic” in the least possible degree’. He was especially excited by the possibilities presented by montage. He also investigated current work on synchronization in the hope of marrying the American composer Georges Antheil’s highly experimental score for the film with the images on the screen. Although synchronization was never successfully realized for the original version of the film, the nitrate version of which is now housed at the Anthology Film Archives, New York and which was first shown on the opening night of the Internationale Ausstellung Neuer Theatertechnik in Vienna in September 1924, the film was often screened with live performances of the score, and later versions feature it as a soundtrack. A fourth vehicle for Léger’s exploration of diverse media was the stage. Léger was fascinated by performance and the possibilities inherent in the visual artist’s collaboration with the choreographer, director, composer and writer. In 1922 his abstract geometric sets and costumes were essential components of the production by the Ballets Suédois of Skating Rink, based on Charlie Chaplin’s film The Rink (1918). In 1923 Léger designed elaborate sets and costumes based on thorough studies of African sculpture for La Création du monde, a Ballets Suédois production based on Cendrars’s collection of creation myths in his Anthologie nègre (1920).

Léger’s collaborative projects culminated in the 1920s with his work for architectural settings. For the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (1925) in Paris Léger was commissioned with Robert Delaunay to produce murals and exhibit easel paintings as part of the décor of Robert Mallet-Stevens’s Pavillon de Tourisme. For the same exhibition Léger exhibited his mural paintings (his most abstract works) along with canvases by Amédée Ozenfant in Le Corbusier’s Pavillon de L’Esprit Nouveau; Léger subscribed in part to Le Corbusier’s and Ozenfant’s notion of PURISM and contributed to the journal L’Esprit nouveau, with which they were associated. These architecturally specific projects were part of Léger’s overall interest in mural painting and his concern for the role of paintings in architecture, particularly in domestic settings. His views were no doubt influenced by his exposure to the ideas of De Stijl, particularly those conveyed through the exhibition of architectural work by this group at his dealer’s Galerie de l’Effort Moderne in 1923. Léger advocated some type of agreement between the architect, the painter and the wall regarding colour, which he believed was a vital component in architecture and absent from much current work. Painters, he argued, could determine its place in architecture better than anyone else.

In 1924 Léger, with Ozenfant, founded the Académie de l’Art Moderne at Léger’s studio at 86, Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs in Montparnasse. Othon Friesz was the third member of the original teaching staff; later Alexandra Exter and Marie Laurencin joined the faculty. Ozenfant left the school in 1929, but Léger continued as its Director until 1939.

iv) 1927–39.

Léger’s involvement with film in the early 1920s led him to place special emphasis on the close-up. ‘The cinema’, he observed in 1925, ‘can become the gigantic microscope of things never before seen and never before felt…. This is the point of departure for a total renewal of the cinema and of the painted picture’. Léger’s fascination with the isolated object increased in the late 1920s, when he embarked on a series of drawings and paintings in which single objects, ranging from a hand to leaves or a bunch of keys, were either seen at close range or were juxtaposed with other seemingly unrelated objects to create jarring contrasts. In drawings, usually made with pencil, these were rendered with great attention to modelling volumes. In paintings, objects were rendered flatly, with strong contours and filled-in colour set against simple decorative planes. Léger’s cult of the object, the phase of his career that came closest to being Surrealist (although he denied any interest in Surrealism), culminated in 1934 with his exhibition Objets at the Galerie Vignon in Paris.

Increasingly in the early 1930s Léger advocated a realism that was more accessible to the people. His major paintings of the decade—Mona Lisa with Keys (1930), Adam and Eve (1935–9; both Biot, Mus. N. Fernand Léger) and Composition with Two Parrots (1935–9; Paris, Pompidou)—depict either instantly recognizable human images or monumental groups. Léger considered this imagery to correspond to a new realism that was appropriate for the masses and that acknowledged the power of contemporary media: film, radio, photography, advertising. Léger’s idealistic views brought him into conflict in the mid-1930s with the more doctrinaire writer and poet Louis Aragon, a strong advocate of Socialist Realism. In the mid-1930s Léger supported the left-wing Popular Front, which came to power in France in 1936, and he attended meetings at the Maison de la Culture in Paris, site of the Association for Revolutionary Writers and Artists. Although he did not officially join the Communist Party until 1945, it is clear that he had been sympathetic to their aims for some time.

Léger’s involvement with film and spectacle intensified in the 1930s. In the early part of the decade he corresponded extensively with the Soviet film maker Sergey Eisenstein. In 1934 he spent several weeks in London preparing to design the sets for Alexander Korda’s film Things to Come (1936); ultimately Korda rejected Léger’s designs, preferring those of both his brother Vincent Korda (b 1897) and László Moholy-Nagy.

During his third trip to the USA in 1938–9, when he stayed with the architect Wallace K. Harrison (1895–1981) on Long Island, NY, and with the left-wing writer John Dos Passos in Provincetown, MA, Léger conceived an animated colour film to be projected within the entrance hall and visible from the escalators of the Rockefeller Center in New York. Projects for the stage also abounded in this period. Léger planned a spectacle on the subject of The Death of Marat, Followed by his Funeral, which he hoped would be executed in the spirit of the painter David; despite his extensive notes for the project and vigorous attempts in the 1930s, it remained unrealized, as did many of his other proposals for the theatre: Le Jeu d’Adam, Parallèle (a ballet) and Le Vélo de fou. In 1932 Léger had also begun a collaboration with the choreographer Léonide Massine for a ballet project that was never realized. Once again collaborating with the composer Darius Milhaud, with whom he had worked on La Création du monde, Léger designed the sets and costumes for the choreographer Serge Lifar’s play David triomphant, which opened in 1936 and was performed at the Paris Opéra in 1937. Also in 1937 Léger produced the décor for Jean Richard Bloch’s Naissance d’une cité at the Vélodrome d’Hiver stadium. This production was among those celebrating the trade unions and was sponsored by the Maison de la Culture.

Léger’s mural for the Palais de la Découverte at the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne in Paris in 1937 was the most massive painting project he had undertaken so far. Entitled Le Transport des Forces (see Descargues, p. 119), the mural is a utopian vision, contrasting the mechanical world, as represented by structures resembling a power station and the forces emanating from it, and the natural world, as seen in the ‘animated landscape’, reminiscent of Léger’s paintings of the 1920s. The mural was one of two realized by Léger for the exhibition; the other was designed for the pavilion of the Union des Artistes Modernes and is known only through an installation photograph. An interview in the magazine Vu revealed that Léger’s ideas for the exhibition had been far more ambitious; he had envisaged 300,000 unemployed people cleaning the façades of all the buildings in Paris and coloured searchlights projecting from the Eiffel Tower at night as loudspeakers played music and aeroplanes hovered overhead.

v) 1940–49.

When the occupation of Paris during World War II became inevitable, Léger travelled first to his family farm in Lisores, Normandy, and then to Marseille and Lisbon, from where he left for the USA in October 1940. The first significant series of paintings Léger began was devoted to Divers and was inspired by the young people swimming off the docks in Marseille. In these paintings large swathes of liberated colour intersect the outlines of stylized figures (e.g. Divers on a Yellow Ground, 1941; Chicago, IL, A. Inst.). Léger sought to free colour from its traditional confines after seeing the effect of neon signs on the activity in the street on Broadway in New York. Work on the Divers theme occupied much of Léger’s time in the early 1940s, and it was followed by his series devoted to Acrobats (e.g. The Four Acrobats, 1942–4; Paris, Pompidou), Cyclists (e.g. The Four Cyclists, 1943–8; Biot, Mus. N. Fernand Léger) and Dancers.

Léger’s years in the USA were dominated by painting, fraternizing with many of the European exiles resident in New York, and teaching and travelling throughout the country. While he maintained a studio on W. 40th Street in New York, he taught at Yale University in New Haven, CT, shortly after his arrival in 1940, and at Mills College in Oakland, CA, in 1941. During the summers of 1943 and 1944 Léger lived near an abandoned farm in Rouses Point, NY, near the New York–Canada border. With French-speaking Montreal less than an hour away, Léger felt especially at home in the region, where he painted a sizeable number of landscapes and object-based paintings. The culmination of his wartime stay in the USA was The Great Julie (1945; New York, MOMA); the painting’s theme is heroicized circus woman Julie, holding a flower in one hand and a twisted bicycle with juggler’s hoops in the other. After completing more than 120 paintings during his exile, Léger returned to France in early 1946, observing that he had ‘painted in America better than [he] had ever painted before’ (see fig. 3).

After 1946 Léger began to participate vigorously in the activities of the Communist Party. Much of his involvement took place in concert with that of the poets Paul Eluard and Louis Aragon; Léger became especially active in causes related to peace, including the first National Council of the World Peace Movement, of which he was a founder-member in 1948. His painting Leisure (Homage to Jacques-Louis David) (1948–9; Paris, Pompidou, see fig. 4) marked a resumption of Léger’s interest in David’s Neo-classicism combined with a large-scale depiction of the common man, from the French bourgeoisie to circus performers and acrobats. After World War II Léger also revived his academy. It reopened in January 1946 in Montrouge, a suburb of Paris, but moved a year later to a larger studio on the Boulevard Clichy in Paris. Nadia Khodassievitch, his student since 1924, directed the academy. Léger had numerous students after the war, including many American artists benefiting from the opportunities available to them under the post-war GI Bill, such as Sam Francis and Richard Stankiewicz. Léger also encouraged workers at the nearby Renault car factory to attend.

vi) 1950–55.

Léger’s concern with the common man culminated in his series paintings of the 1950s: his Builders, Campers and The Big Parade. The Builders is perhaps the best-known series, inspired by Léger’s view of electrical workers perched on poles. Léger made numerous drawings, prints and paintings related to the theme. Eager for these to be seen by ordinary working people, he temporarily installed several of the Builders paintings in the canteen at the Renault factory near Paris, where they met mixed reactions.

During the 1950s Léger also began to work in what were for him new media: stained glass, ceramics, mosaic and tapestry. His initial exposure to ceramics was through a former student, Roland Brice; Léger began to work with Brice during his stay in Biot, between Nice and Antibes on the Côte d’Azur, in 1949. Several of his commissioned works during these years—a mosaic (1949) for the church of Notre-Dame de Toute Grace at the plateau d’Assy in the Haute-Savoie, mosaics (1950) for the Catholic, Protestant and Jewish chapels of the American Memorial in Bastogne, Belgium, 10 stained-glass windows (1954) for the church at Courfaivre in Switzerland and a ceramic (1954) for the Gaz de France building in Alfortville, Val-de-Marne —were made possible by Léger’s newly discovered interest in these techniques. The same was true with his designs for stained glass at the church at Audincourt (1951), Doubs, and at the University of Caracas (1954), Venezuela. Many of these commissions were the result of Léger’s admiration for and friendship with the religious leader Père Couturier, whose friendship with many artists, including Braque and Matisse, resulted in several important post-war projects for churches throughout France. Léger channelled his efforts toward decidedly public presentations through large-scale, prominently placed works. He also continued his involvement with the theatre in his later years, collaborating again with Darius Milhaud on Bolívar, an opera that opened in Paris in May 1950. He designed all of the sets for the three-act opera as well as all 600 costumes. In 1952 he designed an innovative outdoor production of the ballet Quatre gestes pour un génie (music by Maurice Jarre), a homage to Leonardo da Vinci. Léger also became interested again in printmaking at about this time, producing Le Cirque, a series of 63 lithographs with text by the artist, for the publisher Tériade, who had published Matisse’s Jazz in 1947.

Léger’s first wife, Jeanne, died in 1950, and in 1952 he married his studio assistant Nadia Khodassievitch. He continued to produce at a prolific rate and to travel widely throughout Europe until his death.